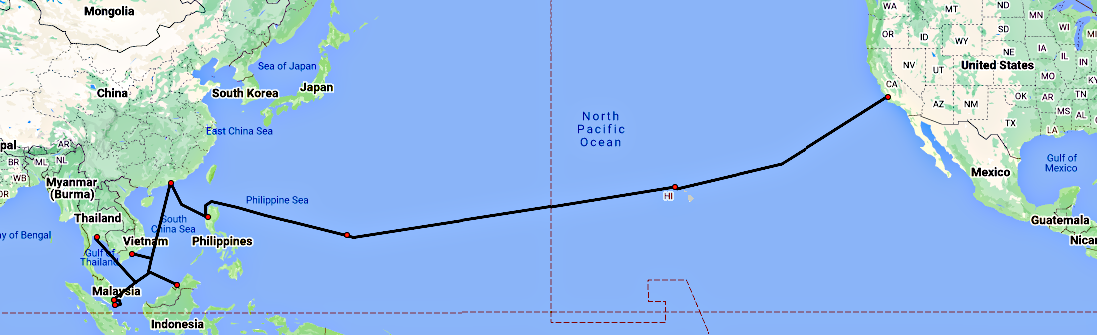

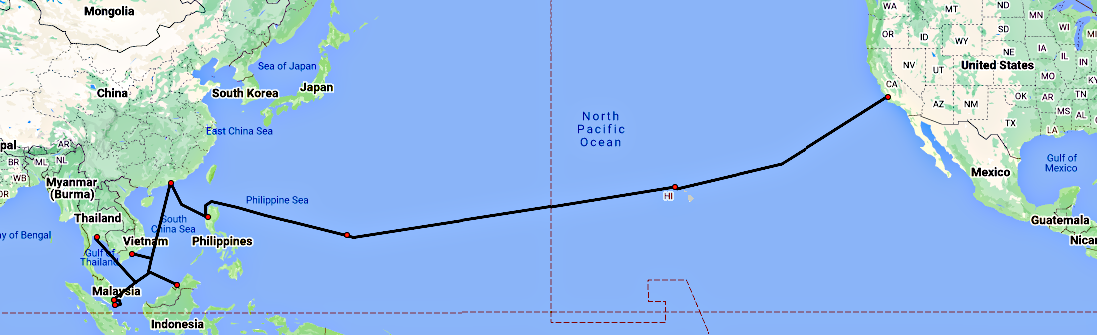

Asia-America Gateway Submarine Cable Network (from “Submarine Cable System Map”, https://www.fiberatlantic.com/system/31wNM ).

Asia-America Gateway Submarine Cable Network (from “Submarine Cable System Map”, https://www.fiberatlantic.com/system/31wNM ).

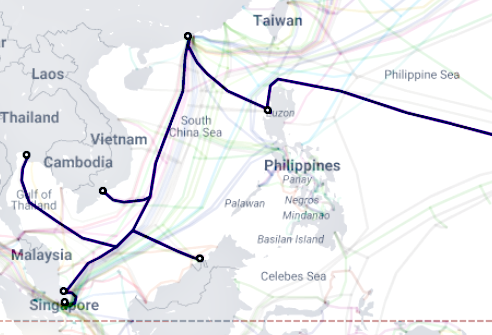

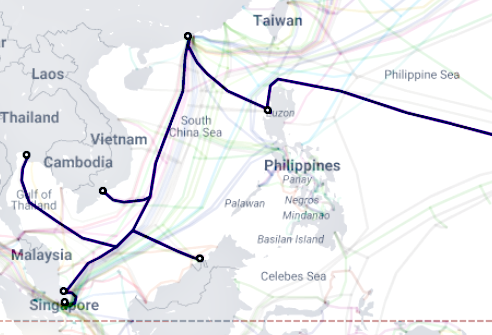

Submarine Cable Networks in the Philippines with AAG Highlightedn (from “Submarine Cable Map”, May 09 2024, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/submarine-cable/asia-america-gateway-aag-cable-system) and Submarine Cable (from “Submarine Cable Repair”, May 28 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=OKS-Hp7q-44 ).

Submarine Cable Networks in the Philippines with AAG Highlightedn (from “Submarine Cable Map”, May 09 2024, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/submarine-cable/asia-america-gateway-aag-cable-system) and Submarine Cable (from “Submarine Cable Repair”, May 28 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=OKS-Hp7q-44 ).

Hyperarchipelago

By Waki Badz

In the contemporary landscape, the locus of media life has shifted decisively to the Internet, ushering in a new era of urban experience. This digital urbanity, as vibrant and toxic as its physical counterpart, saturates our consciousness with its intensity, evoking emotions, segmenting realities, and occasionally injecting humor into our digital interactions.

Drawing from Debord's (2020) incisive analysis:

"Fragmented views of reality regroup themselves into a new unity as a separate pseudo-world that can only be looked at. The specialization of images of the world has culminated in a world of autonomized images where even the deceivers are deceived. The spectacle is a concrete inversion of life, an autonomous movement of the nonliving"

We confront the spectacle—a realm where fragmented realities coalesce into a separate pseudo-world, captivating yet deceptive. This autonomous realm of images distorts life itself, ensnaring both viewers and manipulators alike in its fabricated narrative.

This spectacle becomes a site for the materialization of multiple ideologies which has remodeled itself after a distorted reality. Through Ruy's (2012) notion of object-oriented ontology, I would like to translate this spectacle, along with the geographical insinuations of a physical Philippines, to form an idea of the Philippine Internet as a hyperarchipelago - (hyper)terrestrial separations beyond belief.

For the digital native, the Internet has always been there, a comforting presence occasionally marred by a lost signal.

I. An Internetworking Primer

A. International Links

Under the Sea

Before we go into the historical details, which deal with a few technical terms, let us first discuss what the Internet physically looks like. Back in 2012, Eric Schmidt, who was then the chairman of Google, described the Internet as composed of the Three C’s: Computing, Communications, and Cloud. ‘Computing’ refers to the device that we use, whether it’s a desktop PC, a laptop, or a smartphone. ‘Communications’ refers to the telecommunications medium used to connect the device to the Internet, whether via telephone line, fiber optic cable, or wireless signal. Finally, ‘Cloud’ refers to the computers running the web servers that feed the devices with digital content. The concept is analogous to that of a utility; e.g., an electric utility would have the lights at the home, the power lines running through the streets, and the generator at the power plant. The main difference is that the Internet spans the globe, which means that some of those back end servers are abroad. This is especially true of the Philippine Internet scene. At present, some of the most commonly accessed websites are those of Facebook in the US, Lazada in Singapore, Grab in Malaysia, and Moonton in China.

To allow access to these foreign websites, Internet Service Providers or ISPs connect to submarine cable landing points, of which there are no less than twenty in the Philippines. The submarine cable is a fiber-optic cable capable of carrying terabits (trillions of bits) of data per second. An example is the AAG or Asia-America Gateway submarine cable shown below, which is owned by both PLDT and Globe Telecom, as well as by AT&T and several other foreign telcos. The AAG submarine cable spans 20,000 kilometers and has landing points at La Union in the Philippines, Morro Bay in California, Changi North in Singapore, Mersing in Malaysia, and Lantau Island in China, among others. This submarine cable has a capacity or bandwidth of 1.92 terabits (trillions of bits) per second. To provide a perspective, assuming that the average fixed or mobile Internet subscriber’s bandwidth in the submarine cable’s covered countries is around 20Mbps, this one submarine cable alone has enough capacity to service 96,000 subscribers simultaneously.

B. Local Links

The Mesh

While ‘Communications’ across the ocean looks like a single thick pipe as shown above, ‘Communications’ on land resembles a mesh. The figure below shows a so-called WAN or Wide Area Network that demonstrates the concept of how the Internet works. At each home, devices are connected to a Wi-Fi router. Meanwhile, at each business office, servers are also connected to an office router, also called an “edge router”. Note that the devices plus router inside the home already composes a small network called a Local Area Network or LAN. Likewise, the servers plus router inside the business office is also called a LAN. Each home router is connected by fiber optic cable to a street cabinet. Likewise, multiple edge routers are also connected by fiber to a street cabinet.

Multiple street cabinets, in turn, are connected to a so-called “headend” at a telco Switching Office. The name “switching office” hearkens to the day when telecommunication companies used switching equipment to interconnect individual telephone copper lines. There is usually one switching office per municipality or city. For instance, PLDT has switching offices in Pasig, Cainta, Marikina, Quezon City, etc.

Each switching office in turn connects to each other using a so-called Core Router that interfaces with a fiber-optic backbone network. From the diagram, we can see that the backbone network is in the form of a mesh, with each switching office’s Core Router connected to, not just one, but multiple peer core routers. The purpose of this design is redundancy. Assuming that an employee working from home is connecting to a business office, should one fiber-optic link go down, it is still possible for the signal to reach its destination via a different link. Eventually, via multiple “hops” over various linked routers, the signal reaches its destination. The entire network is called a Wide Area Network or WAN because it covers a wide geographical area.

Another characteristic of the Internet is that it sends its data to and fro in smaller pieces of data called “packets”. This is illustrated in the figure below. For instance, given that a browser requests a web server for a 1-megabyte file, before the web server responds with this data, the server first divides that file into packets of up to 64 kilobytes each, then sends each packet one after the other to the network. The job of the routers is to: first determine the shortest path in the mesh between the web server and the browser, then route the packets accordingly. To do so, the routers, ranging from the edge router at the business office, down to the core routers, and finally down to the Wi-Fi router at home, coordinate with each other, checking if each of them is up or down, and free or congested, to determine the shortest path. Should a link go down at any time, the routers dynamically recompute the route. For each packet received by the device, the device sends an acknowledgment to the server. Should the server fail to receive an acknowledgment from the device, the server considers that particular packet lost and resends it. Finally, once the device receives the final packet, the device assembles the received packets back into the original 1-megabyte file. Due to this request-response-acknowledge method, the system is incredibly scalable and reliable. The more routers there are in the mesh, the faster and more reliable the network becomes

The term used for the above method or “protocol” of data communications is “packet switching”, and the idea has been around since the 1960s, during the height of the Cold War, when scientists and engineers were thinking of a way to make a WAN robust enough to survive a nuclear attack.

Now imagine if the setup above were global; i.e., instead of just a few switching offices, all the switching offices of the world were interconnected into one giant mesh, with some links using submarine cables to span the oceans and seas. We would then have a gigantic WAN interconnecting multiple LANs; i.e., interconnected networks, hence the name “Internet”. All computers at the edge of the mesh would have access to each other. The packet-switching specifications only require that the number of hops be limited to 255, which is more than enough even for two computers half-a-world apart.

Note that “the Fathers of the Internet”, electrical engineer Robert Kahn of DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) and computer scientist Vincent Cerf of Stanford University, designed their protocol called “Transport Control Protocol/Internet Protocol” or TCP/IP back in 1973. The protocol was adopted by the US in 1983. Yet, the Internet reached the Philippines only a decade after that, or in 1994. Below, we discuss why (and it’s likely not what you think).

II. Before the Internet in the Philippines

A. The Protocol Wars (1970s – 1990s)

ITU X.25 vs IETF TCP/IP

TCP/IP was not the only global packet-switching standard from the 1970s to the 1990s. There were actually two competing camps. In addition to DARPA with its TCP/IP protocol, there was also the CCITT (Consultative Committee on International Telegraph & Telephone) with its X.25 protocol. The CCITT was the standardization body of the ITU (International Telecommunication Union), which in turn was an agency of the United Nations (CCITT was later renamed to ITU-T in 1993). CCITT developed X.25 in 1974 and the standard was well-entrenched, especially in Europe.

Being largely a telecommunications standard, it is not surprising that CCITT X.25 was the first packet-switching protocol deployed in the Philippines. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, local telcos PLDT, Eastern Telecom, and Philcom, adopted the protocol and operated X.25 data networks in the country. Since CCITT also had e-mail standards: the CCITT X.500 DAP (Directory Access Protocol) and X.400 MHS (Message Handling System), which ran on X.25, the Philippines had global e-mail and file transfer even back then. The telcos allowed subscribers to access AT&T Mail, MCI Mail, and CompuServe, all of which also ran on X.25. Incidentally, these three American data services allowed X.25 subscribers to send e-mail via X.25-to-TCP/IP gateways to Internet recipients.

In 1988, CCITT also established a set of communication standards called ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network) that allowed ordinary telephone copper lines to be repurposed for simultaneous digital transmission of voice, video, and data, with data, in this case, being via X.25 packets. PLDT also offered ISDN services in the 1990s.

In 1990, CCITT and industry players Cisco, Nortel, and others developed a second-generation X.25 protocol, called Frame Relay, that improved on X.25’s speed by moving data integrity checks to the end nodes. PLDT also offered Frame Relay leased-line services, mainly to banks, in the 1990s until the early 2000s.

Collectively, the protocol standards of CCITT or ITU-T became more popularly known as Open Systems Interconnect or OSI after it was standardized in the 1980s by no less than the International Standards Organization or ISO. In the mid-1980s, it was almost inevitable that OSI would become the global internetworking standard.

However, the problem with OSI was the bureaucracy it entailed since it required agreement among delegates who had competing high-stakes interests, delegates like computer companies and national telecom monopolies. The result was a bloated standard that was too complex to implement quickly. In contrast, DARPA’s TCP/IP, through DARPA’s research task force which later became the Internet Engineering Task Force or IETF, by being largely insulated from politics, was able to quickly plow through the issues surrounding architecture, gateway algorithms, privacy, security, interoperability, and other concerns. Their slogan was “Rough concensus and running code.” DARPA’s polarizing battle with CCITT was dubbed by the networking industry as “The Protocol Wars” (see “OSI: The Internet That Wasn’t”, Jul 29 2013, https://spectrum.ieee.org/osi-the-internet-that-wasnt ).

Starting in 1982, when the US Department of Defense adopted TCP/IP as the standard for its computer systems, DARPA promoted TCP/IP among computer manufacturers like IBM, DEC, and Sun, facilitating interoperability through DARPA’s annual “Interop” event. This later paid off in a big way when CERN in Europe purchased Unix machines for its LANs from 1984 to 1988. Among the machines that CERN acquired was a NeXT Unix workstation with both graphics and TCP/IP networking built in. 1n 1990, with this machine, CERN computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee created HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) and HTML (HyperText Markup Language) on top of TCP/IP. In 1991, Berners-Lee released the World Wide Web application (web server and text-based browser source code), with HTTP and HTML as its foundation.

Two years later, in 1993, software engineers Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina of the NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications) developed a web browser called NCSA Mosaic on Unix X11/Motif that was the first in the world to display graphics inline with the text, and also the first to have intuitive icons for Back, Forward, Home, Bookmarks, etc. They released the Microsoft Windows version in September 1993, and three months later, it landed on the cover of the New York Times’ business section, with the article praising it as “an applications program so different and so obviously useful that it can create a new industry from scratch.” (see “NCSA Mosaic”, Jun 15, 2009, https://www.ncsa.illinois.edu/research/project-highlights/ncsa-mosaic/ ) The World Wide Web became the Internet’s “killer app”, turning TCP/IP into a de facto standard.

Henceforth, TCP/IP’s popularity soared, interest in OSI waned, and the Protocol Wars ended. Thus, in 1994, with no more opposition to TCP/IP, the Internet was free to spread to other countries, including the Philippines.

OSI did not totally disappear, however. Today, we still see traces of CCITT X.25. For instance, the term “Cloud Computing” originated from the X.25 “Network Cloud”. According to network engineer and author Uyless D. Black back in 1988, “[F]rom the point of view of an X.25 user, the network is a ‘cloud’. For example, X.25 logic is not aware if the network uses adaptive or fixed directory routing. The reader may have heard of the term ‘network cloud’. It is derived from these concepts.”

B. Power to the People: BBS

BBS SysOp and Caller (1970s-1980s)

Contrary to popular belief, it is actually possible to have data services even without a packet-switching data network. One way to do so is via peer-to-peer communications, where one user with a computer and modem uses the Plain Old Telephone System or POTS to send messages or files to a similarly equipped peer. Programmer Ward Christensen utilized this setup in 1978 and called it a Bulletin Board System or BBS. The system became popular, and various BBS software packages were developed for different computer models (IBM PC, Macintosh, etc) and operating systems (MS-DOS, MS Windows, MacOS, etc), spreading throughout the world. By 1994, there were 60,000 BBSes serving 17 million people in the US alone. (see “BBS”, Jun 22 2023, https://vintage2000.org/bbs )

In a BBS system, one peer acts as the BBS System Operator or SySop, while the other peer acts as the BBS Caller. The BBS SysOp runs the BBS software (e.g., Renegade BBS on MS-DOS, Excalibur BBS on MS Windows) then waits for a caller. The BBS Caller uses a Terminal program (e.g., Terminate on MS-DOS, or the built-in HyperTerminal on MS Windows) to call up the BBS’s telephone number. Once the two modems finish doing their “handshake” (accompanied by tones on the modems), the caller is able to view the BBS’s main menu and from there, view and post messages on the publicly accessible bulletin board and download and update files. Example BBS Caller and BBS SysOp screens are shown below.

The very first BBS in the Philippines went online in August 1986. It was the “First-Fil RBBS” operated by Dan Angeles and Ed Castaneda using the BBS package called RBBS v.14 on MS-DOS on an IBM PC-XT-clone computer equipped with a 1,200bps modem. It was semi-commercial, with a PHP1,000 annual subscription fee (which would be a hefty PHP8,000/year in 2024 money). It introduced Filipinos to online services like news, messaging, and file transfer. Some BBSs grew to have 8 to 10 telephone lines. (see Jim Ayson, “The State of the Net in the Philippines”, Internet World Philippines ‘96, Sep 23 1996)

BBS E-Mail: FidoNet (1983–1990s)

In 1983, Los Angeles-based artist and computer programmer Tom Jennings started work on his own BBS system which he called “Fido” because it was assembled from various parts, resulting in a “mongrel” system. Due to the high cost of long-distance calls to his fellow developers, he devised a way by which independent BBS systems could call each other autonomously to deliver e-mail in a manner called store-and-forward. He then packaged a Mailer software module that other BBS’s can incorporate into their own systems. The Mailer used a so-called nodelist of the names and telephone numbers of these BBS’s by which they can send and receive e-mails from each other, forming a WAN called “FidoNet”.

Each FidoNet node in the WAN is assigned a FidoNet Node Address of the form

FidoNet reached the Philippines in 1987 with the establishment of the Philippine FidoNet Exchange, which was composed of several BBSs in Metro Manila for local e-mail service. In 1991, the Philippine network connected to the international one. The figure below shows how the hierarchy looked like for some node BBSs in North Manila, Cebu, and, say, Stockholm.

III. The Internet Reaches the Philippines

A. PhilNet Phase 1

Preliminary Research (1990-1993)

In 1990, the head of the National Computer Center or NCC, Dr. William Torres, commissioned a committee study to see if it was possible to have an academic/research network to link Philippine universities and government institutions. The committee, headed by Arnie del Rosario of the Ateneo Computer Technology Center or ACTC, prepared a study of the Internet and received recommendations but no further progress was made. (see “The Day the Philippines ‘Discovered’ the World”, Apr 05 2014, https://newsbytes.ph/2014/04/05/villarica-the-day-the-philippines-discovered-the-world-2/ ). In 1992, Dr. Torres initiated informal discussions with the US National Science Foundation or NSF to bring the Internet to the Philippines (see “Mapua Featured Alumni: Dr. William Torres”, 2014, http://103.29.250.146/cl/alumni_writeup/33 )

One year later, in 1993, Arnie del Rosario brought the project to the attention of Glenn Sipin of the Philippine Council for Advanced Science & Technology or PCASTRD, which is one of the sectoral planning councils of the Department of Science & Technology or DOST. The DOST and a group of universities – Ateneo, De La Salle University, and UP – initiated the formation of PhilNet, the academic/research network envisioned in the original NCC study.

Implementation (1993)

PhilNet was implemented in two phases: Phase 1, which was via dial-up connection, and Phase 2, which was via direct TCP/IP connection. In 1993, for PhilNet Phase 1, the DOST provided a grant of PHP80,000 (around PHP452,000 in 2024 money) to allow the PhilNet consortium to operate a relay hub at Ateneo de Manila University connecting to the Internet via dial-up networking (Unix-to-Unix Copy or UUCP) to a gateway at Victoria Institute of Technology or VUT in Australia, which provided free mailbox service (from ”7 Years of Internet in RP”, Mar 27 2001, https://www.philstar.com/business/technology/2001/03/27/84510/7-years-internet-rp ), and with which AdMU had institutional ties (from “Ateneans Connect to the World”, Apr 14 2014, https://www.philstar.com/business/technology/2014/04/14/1312233/ateneans-connect-world ). In July 1993, with the test a success, other consortium members were able to access the Internet via the relay hub. With this, the DOST provided additional support and PhilNet was expanded to include other universities - University of Sto. Tomas in Manila, St. Louis University in Baguio, University of San Carlos in Cebu, Xavier University in Cagayan de Oro, and Mindanao State University in Iligan City – as well as the DOST itself and the Industrial Research Foundation or IRF. Note that modem speeds at this period were around 28.8Kbps so that was the bandwidth of PhilNet Phase 1. (see “PHNet’s Vision”, Feb 01 2008, https://www.ph.net/about.html )

PhilNet Phase 2

Setup (October 1993 to March 1994)

PhilNet Phase 2 began around October 1993 when the DOST commissioned the Industrial Research Foundation or IRF (which is a foundation under the Industrial Technology Institute or ITDI, which in turn is one of the research institutes of the DOST) to handle the project implementation of PhilNet through a PHP12.5M grant (around PHP70 million pesos in 2024 money). IRF was made in charge of the finances because PhilNet, being a university consortium, had no legal identity by which to accept the grant. The project was then assigned by IRF executive director Cesar Santos to Dr. Rodolfo Villarica, who was one of the trustees of the foundation. (see “The Day the Country Got Hooked”, Mar 24 2001, https://www.ph.net/phildac/Appendices/Appendix%20L.pdf )

Dr. Villarica coordinated with various parties for the requirements of the project: (1) an ISP in the US, (2) an International Private Line or IPL with 64Kbps to link PhilNet to the ISP abroad, (3) local leased lines to connect the various consortium members to the IPL, and (4) routers to be used at the leased line endpoints. For the ISP, the consortium chose Sprint Communications’ SprintLink, which is a Tier 1 global ISP. For the IPL and leased lines, after evaluating five local telcos, they chose PLDT, which offered the IPL for $10,000/month (around $21,150/mo in 2024 money) and the leased lines for PHP130,000 per month (around PHP728K/mo in 2024 money). For the routers, they chose the Cisco 7000 router, priced at $70,000 (around $92,700 in 2024 money), for the main router at the IPL endpoint, and Cisco 2501 routers, priced at $30,000 each (around $63,400 in 2024 money), for the universities. The routers were purchased from Cisco’s authorized reseller in the country, Computer Network Systems Corp. or ComNet.

Sometime in 1993, Dr. Villarica’s friend Dr. John Brule, a Professor Emeritus in Electrical & Computer Engineering at Syracuse University in New York got wind of the PhilNet Phase 1 project. Being a visiting professor over the past 30 years to the University of San Carlos in Talamban, Cebu under the auspices of the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization or SEATO, Dr. Brule thought that it would be a good idea to hold an Internet conference at USC to introduce the Internet to the Philippine academic community. However, since e-mail was the only Internet function available in the country at the time, he decided to call the event “The First International E-mail Conference”, and scheduled it for March 27 to 30, 1994. In October 1993, Dr. Brule met Dr. Villarica, who happened to be visiting his son Marty, a graduate engineering student, at Syracuse University. Dr. Villarica mentioned that he is in charge of PhilNet Phase 2. Dr. Brule, pleasantly surprised, mentioned his planned conference to Dr. Villarica and asked if it is possible to do a live link-up at the conference itself. Being a Cebuano himself, Dr. Villarica also knew some of the people mentioned by Dr. Brule. Thus, despite the tight schedule, Dr. Villarica committed to the live connection in four months. By the end of March 1994, preparations for “The First International E-mail Conference” were underway. Since invitations were sent, not just to members of the academe, but also to members of the PhilNet technical committee, the Philippine FidoNet Exchange, the Computer Enthusiasts & BBS Users group or CEBU, and commercial e-mail service providers, the event was highly anticipated by the Philippine cyberspace community.Launch (March 29, 1994)

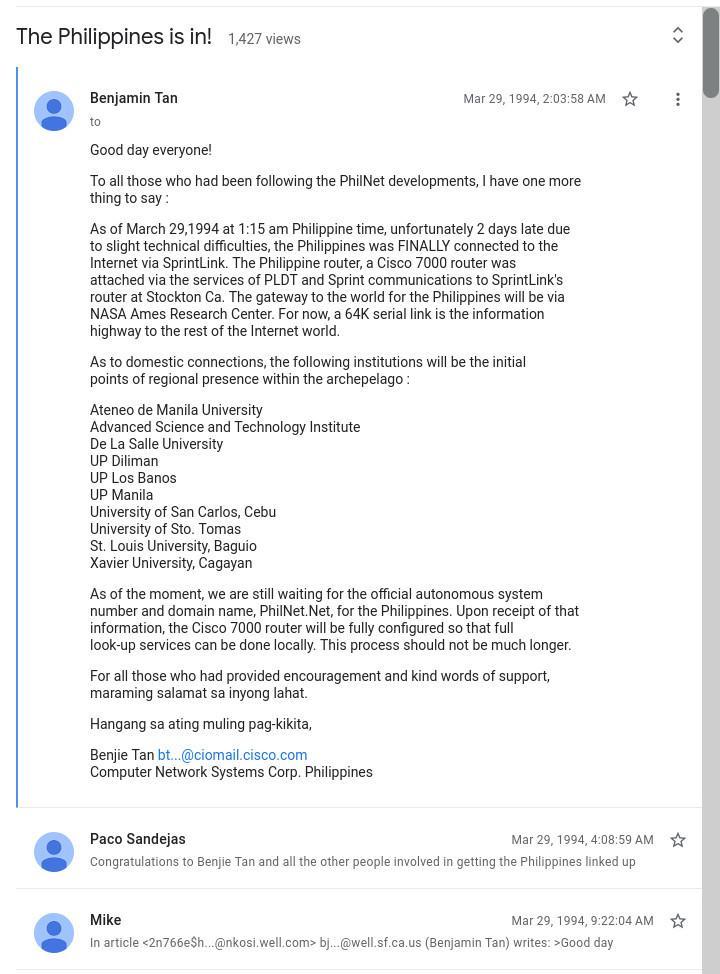

Prior to the conference, Richie Lozada of Ateneo de Manila University flew in and installed a Cisco 4000 router at the endpoint of the PLDT leased line at USC. However, it still awaited the main Cisco 7000 router at the other end. During the conference itself, PLDT was still conducting tests with SprintLink during the past days on the IPL. Dr. Villarica thus anxiously followed up with ComNet in Makati for the router setup. On the evening of March 28 1994, ComNet tech head Benjie Tan got the word from PLDT that the IPL was ready, and readily flew in from a training event in Hong Kong to install the router. At around 11:30PM, he made an IDD call to the SprintLink people in Stockton, California, asking them to be ready to configure the link in one and a half hours. He then disassembled the large and bulky Cisco 7000 to fit in his car and drove with the router to PLDT’s network center at Ramon Cojuangco Building at Ayala Ave in Makati. At the network center, Benjie Tan reassembled the router, after which he and a PLDT technician mounted the router up the assigned rack space, connected the cables, then powered it up. After keying in the configuration parameters faxed by SprintLink earlier, he again coordinated with them via IDD. After SprintLink activated the port at the router at their side, Benjie Tan did a ‘ping’ to confirm that the connection was live, then coordinated with SprintLink for the static routing. At 1:15AM of March 29, 1994, the router work was finished and the Philippines was directly connected for the very first time to the Internet. Benjie Tan celebrated the momentous event with a large Magoo’s Pizza that he shared with the sleepy PLDT technician. While waiting for daybreak, Benjie Tan played with the Internet connection since he had the full 64Kbps bandwidth to himself and it was a far cry from the usual 9.6Kbps bandwidth of a dial-up connection. He downloaded some files to his laptop then sent a message to the Usenet newsgroup ‘soc.culture.filipino’ on the connection (see figure below).

Back to the conference event, at around 5:30AM, Benjie Tan called up Dr. Villarica in Cebu to inform him of the connection completion. He then packed up his things and left PLDT at 6AM. Meanwhile, Richie Lozada, after being informed of the connection, logged into the Cisco 4000 via a workstation at the USC auditorium and reconfigured it to connect to the Cisco 7000. He also reconfigured the conference presentation computer to connect it to the Internet. At 10:18AM, March 29, 1994, on the 3rd day of the conference, USC’s connection to the Internet was also completed, just as Dr. Brule was about to demonstrate live chat. As recounted by IT professional and journalist Jim Ayson, who was present at the event, Dr. Brule “executed the chat commands to chat with his son Mark over at Syracuse [University]. He connected. ‘We’re in,’ he announced.” Immediately after, “an announcement went out, possibly by Dr. Villarica. ‘This is not a dial-up connection. This is the real thing. Our link to the Internet is finally live.’ People were applauding like crazy.” (from “The Day the Country Got Hooked”). The connection setup, as well as the router models used, are shown below.

In 1995, the following year, PhilNet was renamed PHNet to avoid a naming conflict with the “PhilNet” Philosophers’ Network, as well as to avoid a second naming conflict with the similarly named but totally unrelated project called “FilNet 2000”, which was an ill-fated satellite-based trade and industry network initiated by Congress and funded from the Countrywide Development Fund of fifty congressmen (from “The State of the Net in the Philippines”).

IV. User Internet Access

A. User Hardware & Software

WWW, PC, and the Hayes-compatible Modem (mid-1990s)

Internet access in the mid-1990s, not just in the Philippines but all over the world, was mainly via dial-up networking using a so-called “Hayes-compatible” modem. This was identical to BBS access, with the only difference being that the personal computer used had to be capable of running graphics-based Microsoft Windows, instead of text-based Microsoft MS-DOS, since the first popular web browser Netscape Navigator (released in December 1994) and the first popular Internet e-mail client Qualcomm Eudora (released in November 1993 (https://www.historytools.org/software/eudora-guide )), were Windows-based. There were Apple Macintosh and Unix workstation users in the Philippines back then but they were a small minority working in corporate. There were also users of text-based Internet applications like the Lynx browser and the Pine e-mail client but they were also a small minority working in academia.

“Computer Divisoria”: Virra Mall and Gilmore IT Hub (1990s to 2000s)

For computer hardware in the mid-1990s, Filipino users flocked to Metro Manila’s de facto IT hub or “computer Divisoria”, which was Virra Mall at Greenhills Shopping Center in San Juan (from “Retro Computer Groups and Demoscene in the Philippines”, ca 2014, (https://www.reddit.com/r/Philippines/comments/65hgru/retro_computer_groups_and_demoscene_in_the/ ). Virra Mall, which opened in the 1970s, began selling computer hardware, starting with Taiwanese Apple II+ and IBM PC-XT clones, as well as pirated software, in the mid- to late-1980s. By the 1990s, computer stores in Virra Mall were selling not just PC parts but also gaming consoles like the Nintendo FamilyComputer and Nintendo SNES. Since the place was getting too crowded, in 1997, an enterpreneur named Peter Chua opened a computer shop PC Options (with PC being his initials) around 4 kilometers away at Gilmore Ave near Aurora Blvd. PC Options, with its low prices and large volume of sales mainly to PC builders, was so successful that other computer shops like VillMan and PC Express opened branches there as well, turning Gilmore, by the early 2000s, into the next de facto IT hub (from “The ‘IT Hub’ at Gilmore Avenue”, Oct 06 2012, https://www.theurbanroamer.com/the-it-hub-in-gilmore-avenue/ ), even larger than the Virra Mall one. The Gilmore IT Hub holds that distinction to this day (as of 2024).

The Typical Filipino Household PC: Hardware & Software (late-1990s to early-2000s)

The mid-1990s was the time that Microsoft pivoted from multimedia to the Internet. Prior to this, Microsoft was focused mainly on its operating system, office suite, and consumer multimedia products. The success of Netscape Navigator caught Microsoft flatfooted, forcing it to release on May 25, 1995 an internal memo entitled “The Internet Tidal Wave” (https://lettersofnote.com/2011/07/22/the-internet-tidal-wave/ ), which exhorted its employees to catch up with its competitors. By taking advantage of its installed base of around 4 million users of Microsoft Windows 3.1 (released in April 1992), and by pouring millions of dollars in the development of the Microsoft Internet Explorer (released in August 1995) browser and Microsoft Outlook Express (released in August 1996) e-mail client, and then by bundling these programs, sometimes unfairly (see “US Justice Department Proceedings”, Aug 1999, https://www.justice.gov/atr/file/704876/dl ), into the next incarnations of their operating systems, Microsoft Windows 95 (released July 1995) and Microsoft Windows 98 (released June 1998), Microsoft was indeed able to catch up, displacing their competitors’ applications. This explains why, by the late 1990s, the large majority of Internet users, not just in the Philippines but worldwide, all used so-called “Wintel” or Windows and Intel computers to surf the Internet.

Below is a typical pricelist of a computer store in Virra Mall dated February 2000. Note that pricelists, which were updated almost daily, were freely given out at IT-hub computer stores due to intense competition between the sellers. As shown below, Infonet Computers sold both Intel Pentium II- and AMD K6-based PCs. The specs of the typical PC for surfing the Internet was: Intel Pentium II 400MHz CPU, 64MB of RAM, 4MB videocard, 1.44MB 3.5-inch floppy diskette drive, 8.4GB hard disk, 40x-speed CD-ROM drive, 14-inch color monitor, mini-tower casing, keyboard, mouse, and speakers. The price was PHP28,000 (which, adjusted for inflation, would be around PHP60,000 in 2024 money). This did not yet include the modem, which, for a US Robotics 56Kbps External Modem, was priced at PHP5,500 (or around PHP12,600 in 2024 money). Thus, all in all, the hardware to surf the Internet cost PHP33,500 in 2000 money (or around PHP76,700 in 2024 money). It is possible to get a lower price by assembling one’s own computer, and computer stores like Infonet Computers did sell components: motherboards, CPUs, memory modules, diskette drives, hard drives, monitors, etc. Note that an internal modem component like the Motorola 56Kbps Internal Modem sold for only one-fifth the price of an external one (like the Hayes 336 Message Modem shown below). One could also opt for a cheaper “paper-white” (monochrome) monitor instead of a colored one.

Note again that the above did not yet include the cost of software. Fortunately, Microsoft Windows 98 SE (released in June 1999), the license of which cost PHP3,400 in 2000 (or around PHP7,780 in 2024 money) as shown in the Infonet Computers pricelist above, already included the MS Internet Explorer 5 browser and MS Outlook Express 5 e-mail client. These applications were bundled into the operating system, making Netscape Navigator (which was free) and Qualcomm Eudora Pro (which was priced at around USD40 at the time (https://www.qualcomm.com/news/releases/1998/05/qualcomms-eudora-pro-email-40-wins-new-awards-leading-industry-publications )) redundant. Shown below is a typical Filipino household PC ca 2000 running MS Windows 98. This unit was assembled using components purchased from Virra Mall. By this time in the early 2000s, external modem prices have dropped because of the entry of Taiwanese brands like D-Link and Zyxel, which competed with established American brands Hayes, US Robotics, and Motorola. For instance, the D-Link DFM-560EL 56K V.92 Modem used with the unit (as shown below) was priced in 2000 at around PHP1,900 (around PHP4,350 in 2024 money) versus PHP5,500 (around PHP12,600 in 2024 money) for a US Robotics model.

Incidentally, one of the imported components used in the unit above had Filipino origins. The S3 ViRGE (Video & Rendering Game Engine) GPU was designed and manufactured by S3 Inc., which was founded by Filipino electrical engineer Diosdado “Dado” Banatao in 1989 in California as his third startup (hence the name S3), and was one of the first companies to create Windows graphics accelerator chips in the early 1990s (see “Oral History of Diosdado Banatao”, Computer History Museum, 2013, https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2014/07/102746746-05-01-acc.pdf )

Regarding software, the OS installed was MS DOS 6.2 plus MS Windows 98 (with a label on the License Key saying “Not Licensed Outside of the Philippines”). The Internet software installed were the bundled MS Internet Explorer 5 browser and the MS Outlook Express 5 e-mail client. The World Wide Web arose in the mid-1990s right after the spread of home multimedia in the early-1990s. This was fortunate because the latter made CD-ROM drives popular and relatively inexpensive (like modem prices, CD-ROM drive prices went down from PHP5,500 in 1994 to around PHP1,900 in 2000). CD-ROM drives were first sold in the early-1990s as part of PC stereo sound systems, like the Creative SoundBlaster Pro, to allow PCs to play audio CDs and to read software like device drivers and videogames. However, CD-ROM drives were not initially intended to install the operating system itself. The ubiquity of CD-ROM drives at this time made Windows 98 installation feasible for the home and office PC builder. Incidentally, Windows 98 can be installed via diskette drive but it required thirty-nine 3.5-inch 1.44MB diskettes and sixty-six diskette-swaps (see “Installing the Rare Floppy Disk Version of Windows 98, in Real-Time”, Jun 15 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWuJxKtF3gk ), unlike Windows 3.1, which required only six diskettes and less diskette-swaps (from “WinWorld: Windows 3.0/3.1”, 2024, https://winworldpc.com/product/windows-3/31 ).B. Software Piracy

Pirated CD-ROMs (mid-1990s to 2000s)

Users who still found the cost of the MS Windows software too expensive turned to pirated software, which was widely sold at bazaars (locally called “tiangge”) and stalls at malls and public markets. These pirated software were in the form of CD-ROMs and usually originated from Hong Kong, as shown by the Chinese labels on the covers. With the ready availability and low price of pirated software, and the lack of law enforcement to control its spread, software piracy became so rife in the Philippines that up to 77% of installed software in the country in 1998 was pirated (from “BSA Increases Software Piracy Reward to P1M”, Oct 05 2000, https://www.philstar.com/business/technology/2000/10/05/83730/bsa-increases-software-piracy-reward-p1-m ).

Back then and even today (as of 2024), computer stores at both Virra Mall and Gilmore Ave often install pirated software on PC units that are assembled on site. Shown below is an example of a pirated-software CD-ROM used for those installations.

Asia-America Gateway Submarine Cable Network (from “Submarine Cable System Map”, https://www.fiberatlantic.com/system/31wNM ).

Asia-America Gateway Submarine Cable Network (from “Submarine Cable System Map”, https://www.fiberatlantic.com/system/31wNM ).

Submarine Cable Networks in the Philippines with AAG Highlightedn (from “Submarine Cable Map”, May 09 2024, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/submarine-cable/asia-america-gateway-aag-cable-system) and Submarine Cable (from “Submarine Cable Repair”, May 28 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=OKS-Hp7q-44 ).

Submarine Cable Networks in the Philippines with AAG Highlightedn (from “Submarine Cable Map”, May 09 2024, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/submarine-cable/asia-america-gateway-aag-cable-system) and Submarine Cable (from “Submarine Cable Repair”, May 28 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=OKS-Hp7q-44 ).